Between Light and Shadow: Great Sand Dunes National Park - Photographs by John B. Weller

The Creation of Great Sand Dunes

The creation of Great Sand Dunes National Park from Great Sand Dunes National Monument was anything but academic as the expanded park now encompasses the entire watershed upon which the dunes ecosystem depends.

The park’s creation is a unique story, and is being hailed as the wave of the future in land conservation. Organizations and individuals including The Nature Conservancy, the Park Service, scientists, investor groups, local and national politicians, and the citizens of Colorado’s San Luis Valley teamed together to stop a water developer who would have unwillingly devastated the entire dunes ecosystem. Playing complimentary roles, the diverse team was able to raise awareness, buy land, increase knowledge, institute law, and ultimately protect one of our nation’s treasures.

While most national parks are square, following county, state, and other political lines, the serpentine boundary of Great Sand Dunes National Park encircles the ecological, geologic, and hydrological systems that are necessary to sustain the dune system indefinitely. The park is a testament to both nature’s majesty and human dedication to conservation.

Great Sand Dunes is a center. Human remains around the dunes date back 10,000 years. The Tewa Indians considered the dunes to be the birthplace of humanity. Zebulon Pike, on January 28, 1807, wrote “The sand hills extended up and down at the foot of the White mountains…Their appearance was exactly that of a sea in a storm.”

The Experience

A brochure on Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Park might read: “The park is nestled against a backbone of 14,000-foot peaks and boasts a wilderness with a 30-square-mile centerpiece of North America’s largest sand dunes, rich range land, grassland, alpine, riparian, and even wetland ecosystems. It supports a myriad of animal and plant life, including many endemic species. From its fierce localized weather and sand temperatures that range from –28F to 140F, to the delicacy and tenacity of interdunal grasslands, to the unique hydrology of streams that run through the desert, the monument’s natural systems are a unique study in contradictions and interdependence. It is truly a national treasure, and became America’s newest national park in September 2004.”

But this description would just scratch the surface of what is actually out there.

My experiences with Great Sand Dunes National Park essentially started with a frigid November camping trip with a friend. We huddled in sleeping bags on the clean sand of a high dune, but we did not sleep – partially because it was -5˚F, and partially because meteors were streaking the sky all night in twos and threes. I felt peaceful. The next day I walked the winter dunes with my camera, my mind clear and empty. It was as if I had walked into another world. Frost was protected behind each curving ridgeline, reflecting the sky, like pools of deep blue water. My pulse quickened. I had never seen such clean, elegant photographs. Less than a month later, I was back in the dunes again, this time on a four-day trip alone. Again, the images were fresh and amazing. On a still day, I met a pronghorn buck on the dune. Things were making sense.

The more I learned about the dunes the further I wanted to explore. For the next 3½ years, I dedicated one week out of every month to photographing, studying, and writing about Great Sand Dunes. I traveled over sand and under the weight of an immense pack that topped out at 115 lbs., sometimes covering more than 40 miles in a trip. I spent weeks in places that few park rangers have even seen, and in some of the most severe circumstances. In over three years, I saw only one other person. I photographed in 60mph winds with sand swirling so violently that it was hard to breath, in snowstorms with wind-chills of -20ºF, and on summer days so hot that if I were to have lain on the sand, my brain would have actually started to cook. I also saw days so still and crystalline that the only things moving were shadows. I met coyotes face to face, and missed meeting a bolt of lightning by less than a hundred feet. There were times when my hands froze and my eyes filled with sand, but the dunes are constantly changing, and I never wanted to miss the next act.

The Project

It is my goal with the project Between Light and Shadow to both celebrate our newly protected national jewel and help solidify its preservation by raising the awareness needed to ensure wise resource management and respectful use.

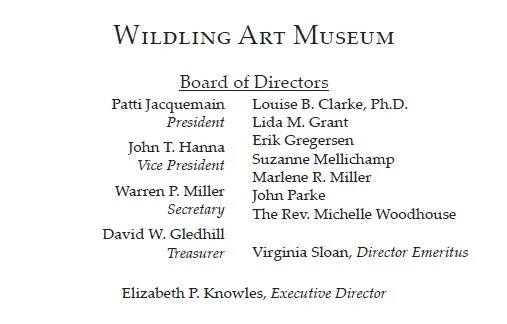

My efforts have resulted in a highly acclaimed book of photographs and creative essays, a film by acclaimed filmmaker Peter Mortimer, and an exhibit of photographs, which, of course, is now showing at the Wildling Art Museum.

The photographs in the exhibit fit together to tell the story of Great Sand Dunes in graphic and vivid beauty. Contradiction and surprise tell of intimacy and grandeur. In the wind-packed cross-bedding exposed by drying sands after four inches of rain, stillness tells the story of motion. In the blurred wingtips of a hummingbird suspended inches away from a flower, motion tells the story of stillness. Light and shadow play hide and seek. A golden eagle soars above silvery midday dunes, wrinkled behind rising heat. Water in the desert reflects dunes along a curving shoreline of rippled sand. Weathered coyote tracks and ten inches of sand-scoured snow masquerade as immense buttes and mesas in a devilish landscape. As a group, the photographs tell a story of balance, revealing secrets and asking questions.